- Views4414

- Likes2

edited by Charlene Rajendran, Ken Takiguchi and Carmen Nge

edited by Charlene Rajendran, Ken Takiguchi and Carmen Nge

Published by Five Arts Centre and Epigram Books Pte Ltd

2018

Review by See Tshiung Han

Krishen Jit casts a long shadow on Malaysian theatre. From 1960 to 2005, he directed 65 full-length productions, restaging Stella Kon’s Emily of Emerald Hill and K. S. Maniam’s The Sandpit four times each. Other plays like Kuo Pao Kun’s The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole, Bernice Chauly’s Three Lives and Syed Alwi’s Tok Perak he directed two or three times apiece. He has shared directing credits with Joe Hasham and Zahim Albakri, artist Wong Hoy Cheong and Singaporean directors Ivan Heng and Ong Keng Sen. With Wong Hoy Cheong, he directed what is arguably the first site-specific performance in Malaysia, Family.

We can know Krishen’s position or speed but never the two at the same time. He seemed to accelerate as he grew older, directing seven plays from 1970–1979 and five plays in the year 1994 and again in 2001. He died in 2005.

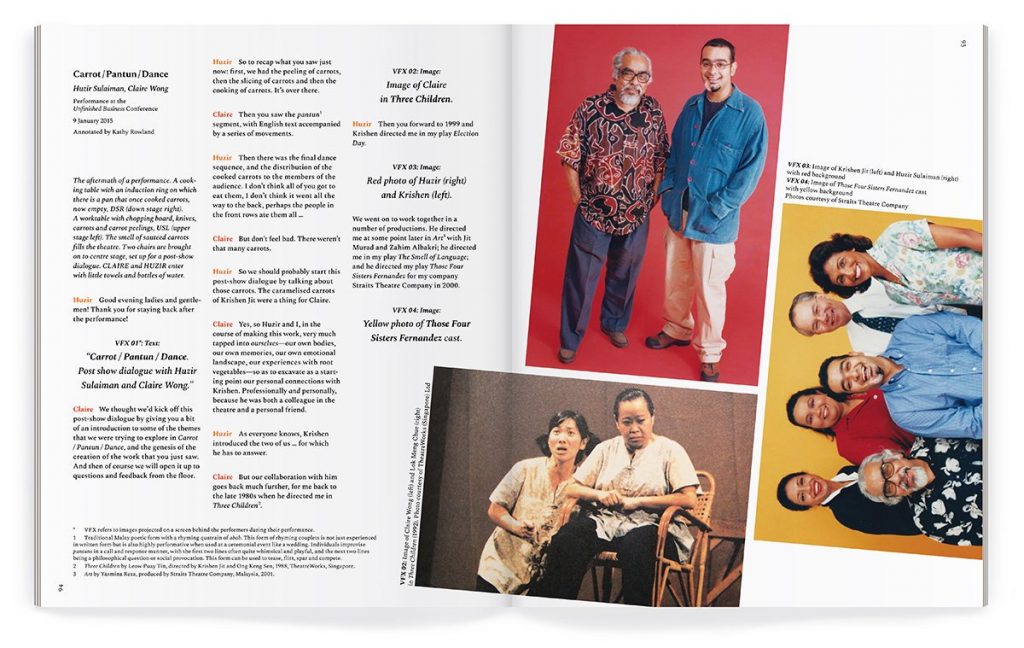

In 2015, Five Arts Centre organized a conference titled Unfinished Business: Conference on Krishen Jit’s Performance Practice and Contemporary Malaysian Theatre as part of their 30th anniversary. The three-day conference opened with a performance by Checkpoint Theatre’s Huzir Sulaiman and Claire Wong and featured keynotes by art historian T. K. Sabapathy and Japanese director Makoto Sato. The conference was a mix of panels, workshops and performances, unlike other academic conferences, which rely heavily on presentations.

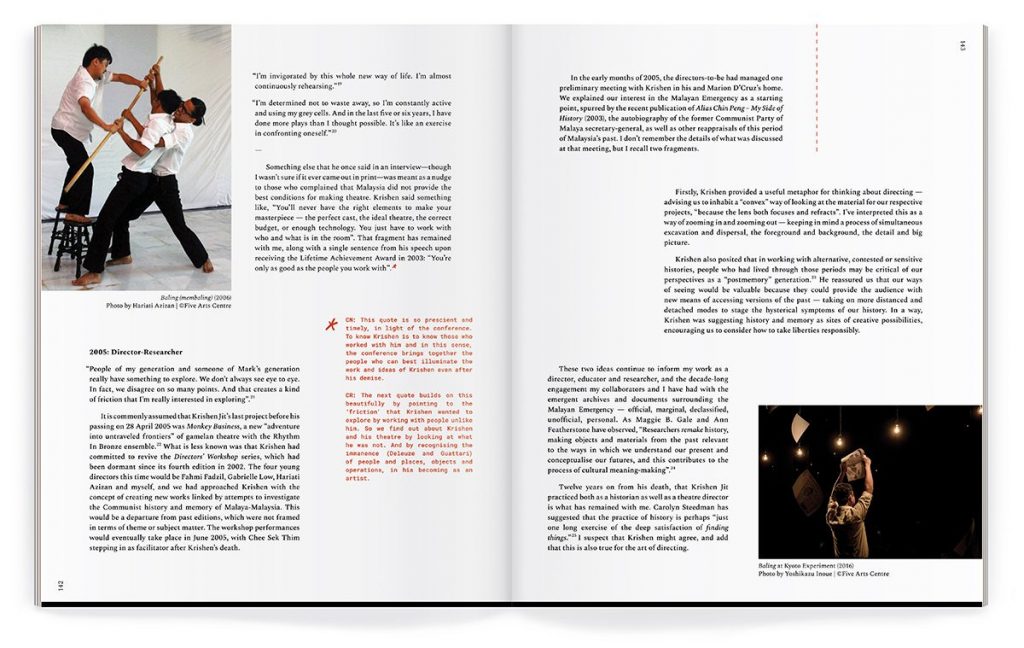

Now, a book about the conference called Excavations, Interrogations, Krishen Jit & Contemporary Malaysian Theatre, edited by Charlene Rajendran, Ken Takiguchi and Carmen Nge, has been published. As wide as A4 paper and 5 cm taller than it is wide, this is a book for contemplation, for laying flat on a table or lap, not for reading on the MRT.

Divided into four sections, the book contains overviews of Krishen’s work and Five Arts Centre as well as transcripts of conference sessions, such as the text of both keynotes and the script of Huzir and Claire’s performance, titled Carrot/Pantun/Dance. The book also contains critical responses to those keynotes and other sessions. Contributors, ranging from director Mark Teh (who worked closely with Krishen in his final years) to meLê yamamo, an Assistant Professor of Theatre Studies at the University of Amsterdam (who never met Krishen and is familiar with him only through his work), weave personal anecdotes together with these critical views to paint a less-than-comprehensive picture of the conference.

This is intentional. Rather than a comprehensive view, the editors give us an idiosyncratic one, more like a collage. We get a mixture of primary and secondary sources. Writers respond to other writers, whether the keynote speaker, workshop facilitators or Krishen himself, in turn generating ideas to be responded to.

Even the designer Zarina Othman can get in on the fun. The text of Sabapathy’s keynote is skewed to the right-hand side of the page, leaving a wide white margin on the left. All 14 pages of the keynote are laid out in this way – why? Perhaps because the keynote is primarily a personal account, although Sabapathy knew Krishen during a critical period in Krishen’s life. By contrast, the layout for Charlene Rajendran’s response to Sabapathy is different. The blocks of text move around the page more freely, signaling to the reader that the response draws on many sources to make its point.

And there are many sources to draw from. Krishen’s roots were planted deeply in Malaysian culture, but they were also planted widely across the region, where he made lasting friendships with other theatre practitioners. Krishen’s relationship with Makoto Sato is one such friendship. Sato’s keynote tells us a lot about Krishen, using the term “sustainable networking” to describe what set Krishen apart from other practitioners. (In 1990, Sato sought out collaborators for a project spanning Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia. He found one in Krishen, who was not dissuaded, as his peers seemed to be, because of the legacy of World War II. Sato’s collaboration with Krishen seemed to grow deeper, thanks in part to Krishen’s vision of an Asian performing arts, no longer dependent on the West.)

We get a lot of personal anecdotes in these essays, but the overall tone is academic. Some readers might be discouraged by critical terms like “phenomenology” or “immanence.” But they should steer into the difficulty instead of away from it. Speaking about the conference, Charlene Rajendran says, it “required the linking up of a lot of dots on your own, and with those present. If you wanted all the dots joined, then it would have been annoying.” The same holds true for the book.

Some of the essays use footnotes, some essays use endnotes; there is no house style here. To complicate matters, the editors have introduced their own commentary, in the form of so-called interventions, signposted by red asterisks, sprinkled sparingly throughout the book.

You may find yourself referring to the endnotes regularly, as I did. All endnotes are located in one section near the end of the book. It may have been better to place them at the end of the essays or at the end of the sections, to minimize flipping around. But this is a book that encourages flipping around. It doesn’t mind putting some distance between a reference and its referent. And happy accidents do occur. You’ll refer to the endnotes for one citation and another citation will catch your eye: I flipped to the back to read more about ARTicle 19 and stayed for the citation about Asian Youth Artsmall.

There is an abundance of negative space on each page, encouraging the reader to insert comments of her own throughout the text. Perhaps this is where the real value of these interventions lie: in showing the reader another way of reading, a participatory way, where she can respond and interact with the information being shown, instead of passively consuming it.

This book fills in a few gaps in the emerging field of Krishen Jit scholarship as well as opening up a few others. Carmen Ng notes, “There have been no analyses of the financial and structural reasons for Krishen doing more work in Singapore.” Some may argue that this is too much granularity, but such a study would shed light on the support systems that Singapore has set up to attract and retain artistic talent, opening the door to Malaysia adopting such systems in the future.

More importantly, if scholars can deploy such resources towards understanding one local theatre practitioner, they might deploy some towards understanding others.

There will never be another Krishen, though. In the same way that Rothko blurred the edges of his shapes so that the viewer is never quite sure where one ends and the other begins, the story of Krishen Jit and Five Arts Centre blur together into the story of a family, a story being played out in smaller scales in artistic communities all over this country. And if any of those communities want to become more resilient – resilient enough to see their 30th anniversary – they might look at Krishen’s work, and start to gather speed.

See Tshiung Han is a writer and editor based in KL.